- DUI

- Criminal Defense

- Florida DUI

- Traffic Offenses

- Drug Charges

- Marijuana Charges

- Violent Crimes

- Domestic Violence

- Temporary Injunctions

- Weapons Charges

- Theft Crimes

- White Collar Crime

- Juvenile Offenses

- Sex Crimes

- Violation of Probation

- Early Termination of Probation

- Seal or Expunge Criminal Record

- Criminal Appeals

- US Federal Offenses

- Misdemeanor Charges

- Felony Charges

- Co-Defendant Cases

- College Student Defense

- College Student Hearings

- FSU Students

- FAMU Students

- Florida Panhandle Arrests

- Extradition to Florida

- Bench Warrants / Warrants

- Emergency Bond Hearings

- Gambling Charges

- Drone Arrests

- Marsy’s Law

- UAS Infractions

- Introduction of Contraband

- Lying to Police

- Locations

- Case Results

- Our Firm

- Media

- Resources

- Blog

- Contact Us

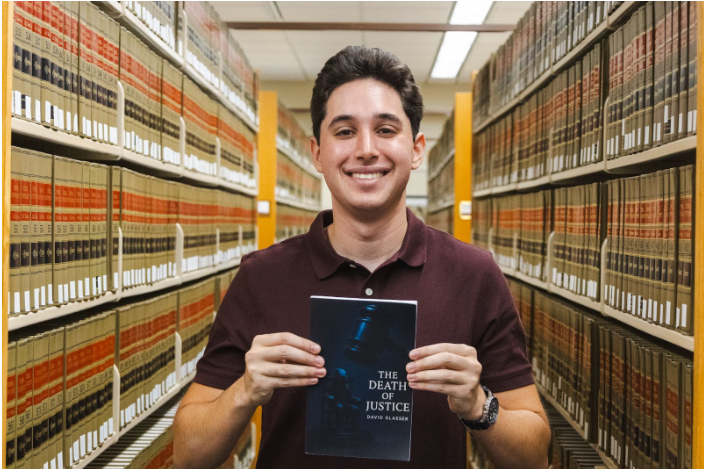

Pumphrey Law Clerk, FSU Law Student Publishes Legal Thriller

July 29, 2025 Don Pumphrey, Jr. Criminal Defense, News & Announcements Social Share

The Death of Justice currently has a 5-star rating on Amazon. It is available for purchase here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FF3PDZVS

While most law students were cramming for exams, David Glasser was doing the same… and writing a legal thriller.

Glasser, a rising third-year law student at Florida State University, is a law clerk at Pumphrey Law. He has worked at the firm for two consecutive summers – and for over 30 hours a week during the school year.

Despite the burdens of law school and a demanding work schedule, an inspired Glasser authored “The Death of Justice.” It tells the story of Jonathan Duggan, a small-town North Florida defense attorney framed for the murder of his wife.

The novel, set in the 1980s, partially derives its plot from a trial he witnessed as a law clerk last year. Published in June of 2025, “The Death of Justice” takes on heavy legal issues ranging from source misattribution, false confessions, and the weaponization (and selective suppression) of evidence at trial.

In Glasser’s book, Florida defense attorney Jonathan Duggan becomes the target of a conspiracy between prosecutors and police, who frame him for his wife’s murder after he secures a shocking and widely publicized mid-trial acquittal. The novel is set in Northam, Florida – a fictional city located just north of Otter Creek.

In addition to being a legal thriller, Glasser says the novel is a commentary on the internal narratives that drive prosecutors and defense attorneys – and the risks that arise when those narratives shift away from making the pursuit of justice their central focus.

“Every criminal attorney, prosecutor or defense, has an internal narrative that drives them to do what they do,” Glasser observed in an interview for the Pumphrey Law Blog. “For those who choose defense work, that often has its roots in preserving liberty and due process, or speaking up for the voiceless. For those who choose to prosecute, it’s frequently the desire to keep the public safe and make sure guilty people don’t get away with crimes.”

“But these tend to evolve over time,” Glasser continued. “And that can be especially perilous when someone is wielding the power of the state. If prosecutors begin to elevate politics or social pressures over pursuing the truly guilty, that’s dangerous territory. In that territory, liberty is often the first casualty.”

“The Death of Justice” employs a dual narrative structure. Readers see both the failure of the system in real time through Duggan’s eyes, and learn of key events in the lives of supporting characters through an omniscient narrator – the identity of whom is revealed at the conclusion of the novel.

“In the book, Duggan wins a couple dozen straight trials,” Glasser noted. “Because of that, the prosecutors and police in Northam decide the humiliation can’t go on any longer. In their minds, Duggan makes it easier for ‘criminals’ to ‘get away with it,’ making him a public safety threat.”

“I hope readers are shaken by Duggan’s suffering. But I also hope they remember his jailors and prosecutors are doing what they feel is best for Northam. And I hope they ask – if politics or what’s ‘good for society’ are elevated above pursuing justice for the individual, what treatment of that individual can’t be justified?”

In addition to being a commentary on how mixed priorities can come at justice’s expense, Glasser says “The Death of Justice” has another warning – this one for every reader who may one day serve on a jury.

“I think we used to live in more of a Perry Mason culture, and now we have a Law & Order culture,” Glasser observed. “Decades ago, most people seated in the jury box were looking at the prosecutor and saying ‘prove it to me.’ In my view, it seems to be a more popular assumption now that the person sitting in the defendant’s chair almost certainly did something to deserve their position.”

“This is especially the case when the charge involves heinous conduct, like murder or a crime against a child,” Glasser reasoned. “So the book is also a reminder that even if we’re rightly appalled by an allegation, the burden of proof – beyond a reasonable doubt – remains the same.”

“When our emotions may push us towards an automatic finding of guilt, the presumption of innocence is especially important,” Glasser concluded. “Otherwise, the jury risks becoming a rubber stamp of the prosecutor when the stakes are highest. That’s the last thing our Founders wanted.”

The Death of Justice currently has a 5-star rating on Amazon. It is available for purchase here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FF3PDZVS